Machine learning insights into molecular science using the Open Science Pool

June 29, 2017Machine learning insights into molecular science using the Open Science Pool Computation has extended what researchers can investigate in chemistry, biology, and material science. Studying complex systems like proteins or nanocomposites can use similar techniques for common challenges. For example, computational power is expanding the horizons of protein research and opening up vast new possibilities for drug discovery and disease treatment.

Olexandr Isayev is an assistant professor at the School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill. Isayev is part of a group at UNC using machine learning for chemical problems and material science.

“Specifically, we apply machine learning to chemical and material science data to understand the data, find patterns in it, and make predictive models,” says Isayev. “We focus on three areas: computer-aided design of novel materials, computational drug discovery, and acceleration of quantum mechanical methods with GPUs (graphic processing units) and machine learning.”

For studying drug discovery, where small organic molecule binds to a protein receptor, Isayev uses machine learning to build predictive models based on historical collection of experimental data. “We want to challenge models and find a new molecule with better binding properties,” says Isayev.

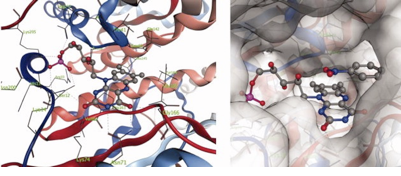

Protein Model

Example of a protein model that Isayev and his group study. Courtesy image.

Similar to the human genome project, five years ago President Obama created a new Materials Genome Initiative to accelerate the design of new materials. Using machine learning methods based on the crystal structure of the material he is studying, Isayev can predict its physical properties.

“Looking at a molecule or material based on geometry and topology, we can get the energy, and predict critical physical properties,” says Isayev. “This machine learning allows us to avoid many expensive uses of numeric simulation to understand the material.”

The challenge for Isayev’s group is that initial data accumulation is extremely numerically time consuming. So, they use the Open Science Pool to run simulations. Based on the data, they train their machine learning model, so the next time, instead of a time-consuming simulation model, they can use the machine learning model on a desktop PC.

“Using machine learning to do the preliminary screening saves a lot of computing time,” says Isayev. “Since we performed the hard work, scientists can save a lot of time by prioritizing a few promising candidate materials instead of running everything.”

For studying something like a photovoltaic semiconductor, Isayev selects a candidate after running about a thousand of quantum mechanical calculations. He then uses machine learning to screen 50,000 materials. “You can do this on a laptop,” says Isayev. “We prioritize a few—like ten to fifty. We can predict what to run next instead of running all of them. This saves a lot of computing time and gives us a powerful tool for screening and prioritization.”

On the OSG, they run “small density function (DFT) calculations. We are interested in molecular properties,” says Isayev. “We run a program package called ORCA (Quantum Chemistry Program), a free chemistry package. It implements lots of QM methods for molecules and crystals. We use it and then we have our own scripts, run them on the OSG, collect the data, and then analyze the data.”

“I am privileged to work with extremely talented people like Roman Zubatyuk,” says Isayev. Zubatyuk works with Isayev on many different projects. “Roman has developed our software ecosystem container using Docker. These simulations run locally on our machines through the Docker virtual environment and eliminate many issues. With a central database and set of scripts, we could seamlessly run hundreds of thousands of simulations without any problems.”

Finding new materials and molecules are hard science problems. “There is no one answer when looking for a new molecule,” says Isayev. “We cannot just use brute force. We have to be creative because it is like looking for a needle in a hay stack.”

For something like a solar cell device, researchers might find a drawback in the performance of the material. “We are looking to improve current materials, improve their performance, or make them cheaper, so we can move them to mass production so everyone benefits,” says Isayev.

“For us, the OSG is a fantastic resource for which we are very grateful,” says Isayev. “It gives us access to computation that enables our simulations that we could not do otherwise. To run all our simulations requires lots of computing resources that we cannot run on a local cluster. To do our simulation screening, we have to perform lots of calculations. We can easily distribute these calculations because they don’t need to communicate to each other. The OSG is a perfect fit.”